Summer in the northeast is transformative. The earth seems to come alive again; trees are green, flowers are blooming, and monarchs have arrived.

One of the most easily-recognizable insects, the monarch butterfly, makes its summer home in several parts of the United States and Canada before returning to Mexico for the winter. This cyclical migration spans 3,000 miles, 3 countries, and several generations of butterflies. But in recent years, fewer and fewer monarchs seem to be making the trip. It’s estimated that the current monarch population is only around 10% of its historic numbers due to pesticide use and habitat loss.

Pollinators like butterflies are vital to a healthy ecosystem, so this decrease in population is a cause for concern and a sign that the monarchs need our help. I wanted to do my part in ensuring a few more caterpillars made it into adulthood. To do this, I had to find eggs, raise the caterpillars all the way through pupation, and finally release the butterflies back into the wild. This blog is the first in a several-part series where I spend half of my summer “raising a monarchy”.

To find eggs I needed to find the monarch caterpillar’s main source of nutrition- milkweed. Milkweed is a flowering plant that comes in a few native varieties, all of which can support monarchs. In fact, this toxic plant is the only thing these guys will eat. Moms like to lay their eggs on the leaves of milkweed so when larva hatch they can get right to munching, which along with sleeping, pooping, and molting, is pretty much all they do for a couple of weeks.

I’m lucky enough that my office is located at the Hilltop Hanover Farm which boasts both a pollinator garden filled with milkweed and a meadow habitat where it grows freely. After doing research on how to identify milkweed and monarch eggs, I spent one afternoon combing through the wild milkweed at the farm, looking for eggs, caterpillars, and butterflies. I found nothing.

Perhaps the monarchs just didn’t like that spot? I went to the pollinator garden, which I had told myself I would leave alone, since people had worked very hard to plant and grow those flowers. More than anything, I was just curious if monarchs had made it to this space specifically designed for them. Again, I came up empty handed.

Where was everybody? I didn’t see a single monarch flutter by or even one plump caterpillar chomping on a leaf, let alone a teeny tiny egg waiting to hatch. Slightly defeated, I went back inside and did more research. Was I mistaken when I thought I could see monarchs this time of year? Had I misidentified milkweed? No, it seemed my information was right the first time around, and that was definitely milkweed growing out there. Maybe I was just feeling the effects of a monarch population decline, and finding them would be harder than I thought.

Salvation came in the form of an email from a former coworker who had seen monarchs flying in the Leon Levy Preserve in Lewisboro, NY. He told me that if I was looking for monarchs I should check out their trails, so to their trails I went. I also did some nature journaling there, too.

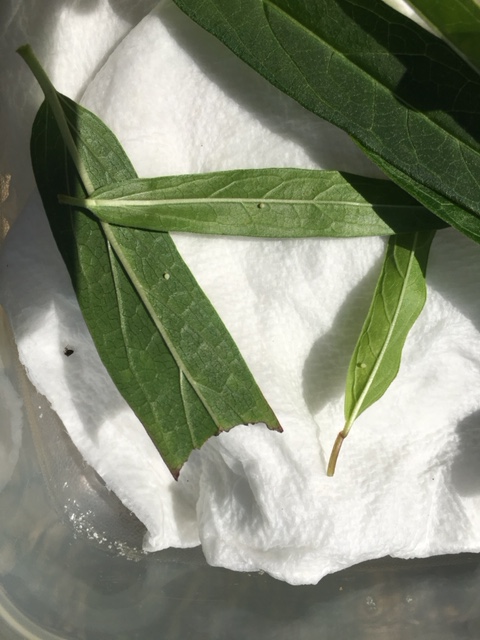

I had to check a few different milkweed plants at Leon Levy, but eventually I saw caterpillars. I was relieved. If there were caterpillars, there had to be eggs. I could’ve settled for rearing already hatched larva, but for the purpose of this blog I wanted to capture the entire life cycle. I flipped over leaves; some unfortunately covered with destructive aphids, and finally found 3 eggs to take home.

I put the entire leaf with the eggs on them in a small Tupperware container and before the night was even over, I noticed one of the eggs had gone dark on top- a guaranteed sign the caterpillar inside was about to hatch. And sure enough, when I checked on the eggs the following morning, the tiniest little wiggle had already emerged from one of them.

So what do you do once the egg hatches? Check out my next blog to find out.