Volunteers up and down the Hudson Valley are on the hunt for a smelly sign of spring.

In winter of 2025, I signed up with a community science project to help to collect data about one of the most unique plants in our forests: Symplocarpus foetidus, AKA eastern skunk cabbage. If you spend any time in the woods from March to May, odds are you’ve seen this unusual plant and its speckled, purple spathe or its lush, green leaves. Maybe you’ve smelled the pungent aroma that gives skunk cabbage its name or seen large patches of it growing in its preferred habitat of forested wetlands. Sensorially speaking, it’s a hard plant to miss.

Eastern skunk cabbage in full leaf out. Photo by Kurt Andreas.

Dr. Joanna Coleman, the Principal Investigator on this project and an urban ecologist at Queens College, is researching the impacts of urbanization on skunk cabbage (SC) in and around New York City. Along with coauthors and investigators Gretchen Begley, Matthew Stanton, and Sophie Barno, Dr. Coleman and her team began to study how the urbanization side effects like the urban heat island, light pollution, and soil composition, could impact flowering times of SC. Skunk cabbage is one of the first plants to bloom in our woods, so a changing climate, for example, could shift flowering times and cause it to fall out of sync with other seasonal changes.

Skunk cabbage emerges in winter, where even a blanket of snow on the ground isn’t enough to stop it. Sometimes you can see the purplish spathe, which is a modified leaf, push up through the late winter snow. This process is made possible by a phenomenon called thermogenesis. Thermogenesis is when an organism uses its metabolism to raise its internal temperature higher than that of the ambient temperature around it. It’s a survival trait we share with SC, which is essentially a warm-blooded plant. But in world of increasingly short, warmer winters, would thermogenesis continue to be an evolutionary advantage? And would it disrupt the typical flowering times for this hardy, little plant? These are only two of many questions this on-going research hopes to answer.

As volunteers, our job was to visit the same patch of skunk cabbage on the same day every week in late winter and early spring to take pictures of the same individual plants. Then, we’d determine which flowering phase each plant was in and upload the pictures to a form managed by the researchers, who would compile and double check our work. But before we began collecting data, we had to brush up on our SC anatomy and life cycle.

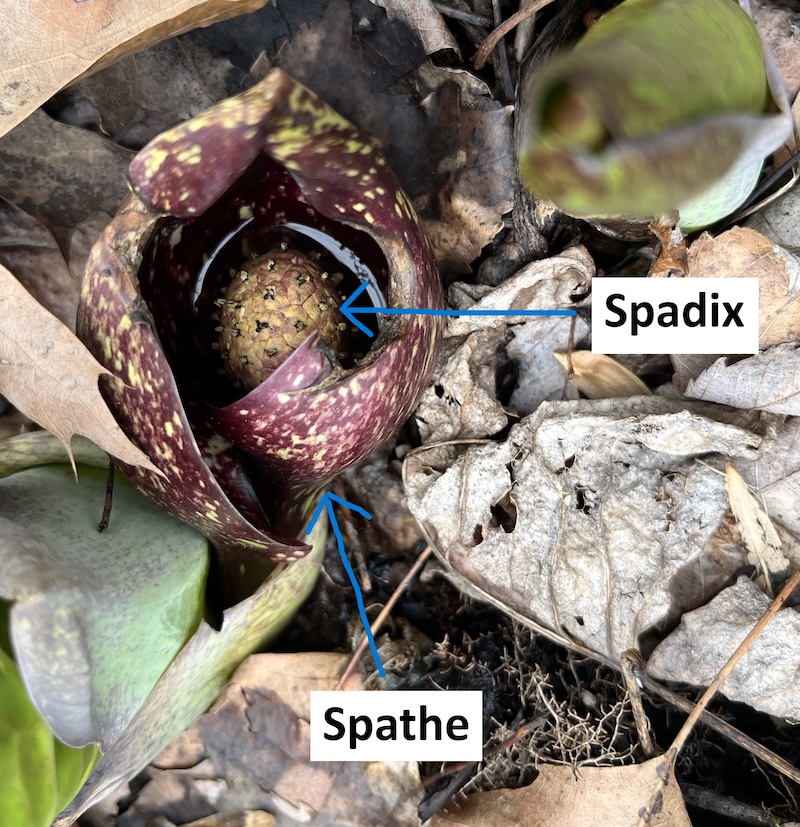

The parts of the plant we’d be looking at were the spathe and spadix. The spathe is the modified leaf that protects the spadix, or the flower structure.

The spadix is nestled inside the spathe.

The Queens College team taught us that skunk cabbage flowers in the same order every year. This means it has regular phenophases, or life stages. The phenophases are:

- Immature- no flowers are visible and the spathe is tightly closed.

- Female- small stigma are clustered together in one grouping of many, tiny flowers. This flower structure is the spadix.

- Male- anthers replace the stigma. These are larger and more visible than the female flower parts, and they’re full of pollen

- Done flowering- the spadix has begun to dry up and blacken.

- Fruiting- this happens later, towards the end of the summer.

While at first this process felt straightforward, I soon realized that it was much tricker to identify the flowering stages of SC than I originally thought. As it turns out, sometimes skunk cabbage skips certain phenophases, and sometimes two stages look much more similar in real life than they do in a textbook diagram. I knew the flowering would always happen in the same order, but I didn’t know how long it would take for a flower to move from one phase to the next. It wasn’t always clear to me if a female plant one week could still be female the next week, or if it could have already gone through the male phase by the time I rechecked it and now it was done flowering. Sometimes the spathe hardly opens and it’s difficult to get a clear view of the spadix inside, and sometimes the SC is surrounded by muddy water or poison ivy, making it difficult to get close to.

These are all pictures I took during the research project. Can you identify the phenophases of skunk cabbage? Answers are at the bottom of the blog.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Despite the challenges, each week I did my best to pin down what the flowers were up to. We were provided with a small camera that could fit inside the tiny spathe to take pictures up close, which left me with some very alien-looking shots of the spadix, like the ones above. Eventually, all the spadices darkened and the spathe around it began to get soft and mushy. Flowering time was over, and soon only the leaves would be present.

Watching one plant up close for an entire season helped me focus on the seasonal changes the world goes through in spring. My first few visits were misty, cold, and dark. Rockefeller Park is in Sleepy Hollow Country, and it was easy to look down foggy, forested trails and twilight-lit fields and understand how this area inspired one of the most famous ghost stories in the world.

I could’ve sworn I saw the Headless Horseman on this trail.

About halfway through my data collection, turtles and birds began to arrive, and suddenly the walk to the research plot included bird watching and turtle spotting. Rockefeller Park’s Swan Lake is known for its bird diversity, and one walk around the lake makes it easy to see why. Great blue herons, wood ducks, mallard, cormorants, Canada geese, red-tailed hawks, and more could be found in and above the water for weeks on end. By the time the skunk cabbage was fading, I had swapped my microspikes and winter coat for sneakers and a windbreaker. Rockefeller had defrosted, and the skunk cabbage study period had closed for the season.

It won’t stay closed forever, though. Researchers are still collecting data about skunk cabbage, and they plan to do another round of community science in 2026. If you want to get involved with the project, you can reach out to the investigators and learn more here. If you can’t participate but still want to study the phenological changes of your local environment, we have some how-to information on how to get started here.

Answers: 1. Male 2. Immature 3. Female 4. Done flowering 5. Trick question- this one is transitioning from female to male. Notice the change from the stigmas on the top half of the spadix to the anthers on the bottom.