A thorough look at a white ash and hemlock harvest on a property in the Catskill Mountains.

Part 1 – The Harvest

The year we bought our house here was 2008, not too long before the Emerald Ash Borer (EAB) was first discovered in the Catskill Region. The ash trees we decided to cut were roughly 60 to 90 years old and decades from reaching financial or biological maturity, but with EAB looming and other factors, we moved ahead with the harvest that netted roughly $8,000 for the entire nine acres we cut and left us with plenty of firewood to heat our home, open views into the woods from our house, and new trails. All told, about 150 ash trees were cut, skid and hauled out to be milled into lumber, baseball bat blanks, or processed into firewood. We also thinned in the hemlocks. The open light conditions won't produce reishi mushrooms for a while like what I picked and processed before the cut, but like everything, there's a tradeoff. I wanted to let more light in to create conditions for some diversity within the stand as a hedge against the hemlock woolly adelgid with warmer winters expected in the future.

Medicinal reishi mushrooms growing on a decaying hemlock in the damp conditions of our woodlot. June, 2020.

The logs were cut with a chainsaw and yarded with a small cable skidder or sometimes a small bulldozer to a spot up the hill on our neighbors’ land, a participating farm in the Watershed Agricultural Council’s (WAC) Conservation Easement program. WAC foresters worked with my logging contractor and I to advise trail construction and closeout using water diversions installed with a bulldozer after the cut. Roughly $2,000 in best management practice (BMP) cost-share funding was provided to the logger to offset his costs for trail grading and closure. Here is a link to WAC’s BMP cost-share program for timber harvests on private land in the New York City Watershed.

Aside from some equipment breakdowns that stalled the project, the whole harvest was wrapped up in 6 months (during the economic distress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic). Here are some photos of the project at different phases and what products resulted from it…

A day after the main skid trail was roughed in with a bulldozer, 2 to 3 inches of torrential rain made a mess of things for a while and the operation was temporarily shut down to let things dry out. August, 2020.

The Timberjack cable skidder awaits a hitch of hemlock logs to pull to the landing. August, 2020.

Some areas received a thinning where the ash did not dominate the stocking, while in other areas trees were removed in small groups. September, 2020.

At the landing, the trucker sorts products into neater piles for future handling. On the left is hemlock pulp, at the back right are sawlogs and in the right foreground is hardwood firewood typically cut not to exceed 16 feet in length. October, 2020.

A load of hemlock logs from our woods are transported to a sawmill about 10 miles away. Each truck holds roughly 4,000 board-feet, a common lumber measurement equaling a board that is 12 inches wide by 12 inches long by 1 inch thick. The truck weighs around 70,000 to 80,000 pounds fully loaded. November, 2020.

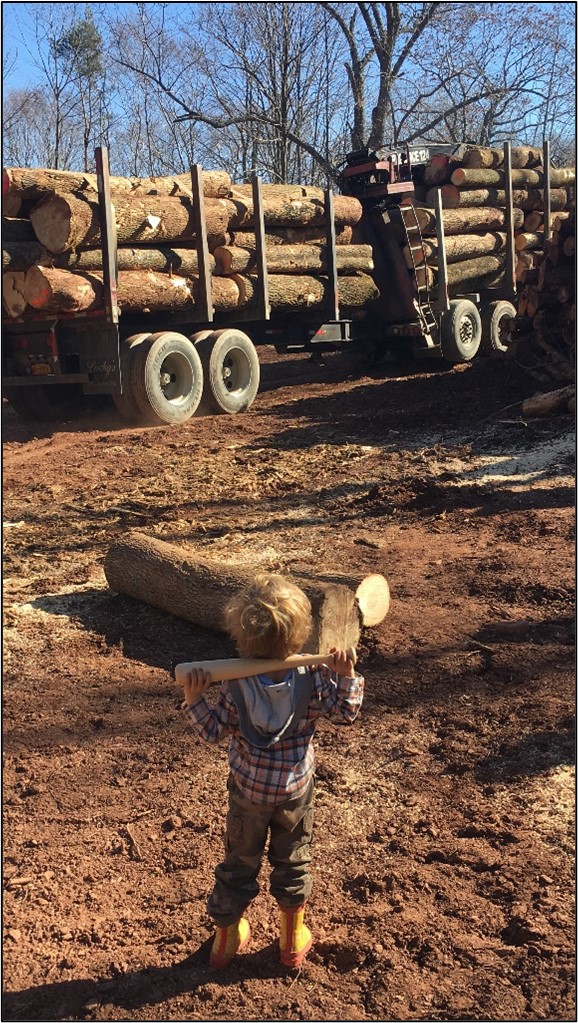

My son and I followed the trucker over the hill to watch him unload at Peterson’s Mill in Jefferson, NY. Upstate New York has dozens of smaller mills that produce boards and beams for local building projects using rough cut hemlock and pine…projects that will continue storing carbon throughout the lifespan of the building(s). November, 2020.

With over four inches of sapwood (lighter colored wood on the outside), this eighty-year-old ash (note the rings we counted) was one of a few we cut and sold at a premium to a local factory called Leatherstocking Hand-Split Billets that makes and dries billets for use in professional and semi-professional baseball bats. My son came in for a closer look at the rings with the lighting just right for a silhouette. November, 2020.

Each log is inspected for defects, measured, and graded accordingly at the landing. Often this is done at the mill, but in this case, the buyer came to the landing for the first load, so he could develop a rapport and build trust with the logger (a new supplier) in hopes that he might send in more loads. It also helps when there’s a souvenir bat involved. November, 2020.

The largest ash in the project, 26 inches in diameter and about 100 yards from our kitchen window, had a seam running down the middle of it to indicate it had been struck by lightning earlier in its life. Whereas all the other trees were destined for the sawmill, this tree was marked “F” as I had it picked out to make new flooring for our house. Before it was cut, my then four-year-old son took a charcoal bark rubbing, a suggestion from the former editor of Northern Woodlands Magazine, Dave Mance III in his eulogy for ash. January, 2021.

As logs lose moisture, the wood shrinks and can crack. Since we waited almost 3 months for the final cleanup at the landing when a truck could load my logger’s dump truck, these ash logs were stamped with metal “S” irons to limit end checking that can waste lumber and de-grade the log. Note the seam along the left side of the logs as they were moved around the yard before processing at Biruk Lumber in Halcottsville. Each log will receive a coating of wax on each end to trap more moisture from escaping before sawing.

After custom milling, kiln-drying, installation and finishing, we ended up with about 400 square feet of random width flooring for our living room and small office (not pictured) and custom treads and risers for our bedroom stairs. We only ended up with two leftover boards, which I used to make some shelves. Pretty efficient, I’d say!